(For more background on the FDC3 standard - see our previous history of FDC3 post)

AI is disrupting everything in the SaaS space - this is not news. Integration and engineering problems that once required thoughtful, skilled, and time-consuming attention are now solved by coding agents in minutes.

These developments have had two contradictory impacts on the future of the FDC3 standard.

Which one will be FDC3’s legacy? That’s going to depend heavily on what parts the community pushes forward and how the standard and its implementations adapt to the move from an app to an agent-centric topography.

The FDC3 standard originally described what was termed a ‘desktop agent’. This was a direct reference to the W3C ‘user agent’ terminology and meant to distinguish an FDC3 implementation not only with a different set of capabilities from a standard browser - but as an agent of the ‘desktop owner’. i.e. an enterprise organization (a very different scope from the user scope of a commercial browser). The desktop agent looks across its ecosystem and determines what (user, application, or agent) can interoperate with what. While the desktop-centric terminology is dated, the need for a durable interoperability layer is far more relevant today than it was in 2017 when the standard was created. The difference: back then, we were thinking in terms of apps. Today, our primary (and just about singular) use case is agents.

Connectifi’s founding objective was to take this interoperability layer and move it off of the desktop so that it could be distributed, managed, and observed all while being tech agnostic at the client/application layer. Interestingly, we’ve seen the same patterns and sets of needs surface with the AI interoperability standards. Especially as tech like MCP moves off of desktop only set ups to remote and mixed scenarios required for enterprise deployments.

FDC3 as a protocol / developer API made sense in the world of financial applications, where orchestration across the desktop ecosystem to form complex dashboards and screen interactions across scores of apps was the goal. LLMs and agents are already upending this model, you don’t need a human monitoring dozens of apps across multiple screens when an agent can do this far more effectively without requiring the deep tech investment, UX engineering, and heavy TCO. While the form factor has changed, the need for interoperability standards hasn’t gone away. Those scores of end-user facing applications are being replaced with an ever growing number of agents that need to orchestrate with each other, and - occasionally - a human in the loop.

MCP, A2A, and others have come together fast to fill many of the standardization gaps for AI that FDC3 had addressed for financial applications. While, the momentum is clearly with the AI standards, there are some lessons learned from FDC3 that remain highly relevant:

The original scope of FDC3 was focused on 3 major themes that have parallels in the emerging AI standards today. Generally, these are:

Discoverability

In FDC3, applications can discover and call capabilities from other applications. This is done through a directory of applications and their supported intents and brokered by the ‘desktop agent’. Because applications can discover and connect to other applications based on business functions, application engineers and end users alike don’t need to know the technical details of these ecosystems. Instead, they are free to focus on the workflow at hand.

Dynamic Tool Selection

At the core of FDC3’s intent system is the idea that multiple applications can fulfill the same function and that a choice can be made by the end user - mirroring intents in mobile applications. Dynamic tool selection also means that workflows can be described once and then run adaptively with different toolsets depending on what’s available to the specific user and environment.

Native UI Integration

FDC3 supports application integration from application front ends, allowing integrations at the last mile that work on what the end user is actually interacting with. This allows for a user experience that feels native to the integrated application. Menus, calls to action, data, can all be presented where the end user is, without additional layers of abstraction or indirection.

We can see parallels of these FDC3 concepts in ongoing efforts with A2A, MCP, and WebMCP today. Ultimately, if agents are going to support broad discovery and interoperability, if end user applications are going to support programmatic integrations with LLMs, if end users are going to be able to swap toolsets in re-playable workflows, a common language will go a long way in enabling this.

FDC3 set out to provide a domain-specific vocabulary for financial workflows. Even within that relatively narrow scope, creating a durable shared language proved hard. Any attempt to standardize object models across organizations and applications inevitably collapses to the lowest common denominator—and that is an inherently lossy exercise. Strip out too much expressiveness, and local dialects will creep back in out of necessity, expediency, or simple economics. Sometimes all three.

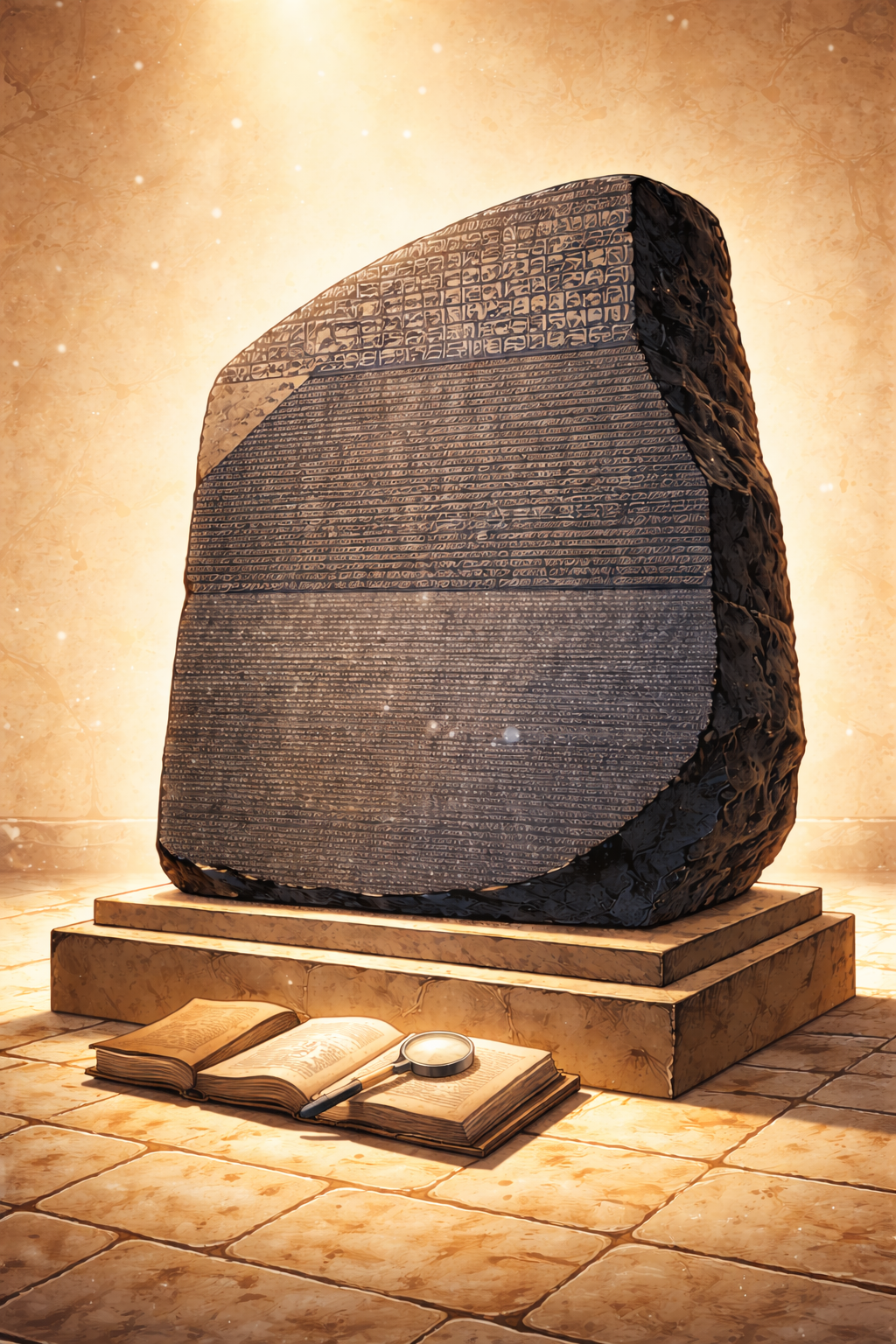

This is the “Esperanto problem.” Standards that aim to be neutral, universal, and conflict-free often end up abstracted to the point where they work well for no one. They avoid disagreement by saying less, not by enabling more. Adoption stalls, and the real semantics move elsewhere—into proprietary extensions, side channels, or undocumented conventions.

LLMs give us an opportunity to approach this problem differently.

Rather than forcing every domain into a single, globally agreed DSL, we can flip the model. Each domain can retain its own rich, expressive vocabulary—its own dialect—and present that to agents via a shared translation layer. In this model, the standard doesn’t try to be the language everyone speaks. It becomes the Rosetta stone that allows languages to coexist.

Concretely, this suggests a layered approach:

In this world, interoperability doesn’t depend on everyone agreeing on what an “instrument,” “case,” or “customer” really is. It depends on being able to describe intent, context, and capability clearly enough that an agent can reason across those boundaries. The lossiness moves from the standard to the translation layer—where LLMs are uniquely well suited to absorb it.

This is where FDC3’s legacy may still matter.

Not as a universal protocol competing with MCP or A2A, but as a set of hard-won lessons about discoverability, intent, and semantic alignment—reapplied to an agent-first world.

Build with Connectifi and let us help you, accelerate time to value, remove complexity, and reduce costs. Talk to us now.